Is Solarpunk 21st Century’s science fiction?

by Romina Braggion & Franco Ricciardiello, from Robot magazine no. 91. Translation by Antonio Ippolito

Solarpunk is not just a subgenre of science-fiction. It is an intellectual movement and an aesthetics declined in several forms of art. It addresses a clear demand for hope in the future, and represents a reaction to dystopia by the new generations; it takes form as a futuristic imagination not blindly positive, but at least better than the present, sustainable, democratic; in a word, solar.

If a Cartesian map of science-fiction existed, the solarpunk movement would probably be at the opposite extreme of dystopia, whose great fortunes we have observed in the last years: born of a noble rib of science fiction—Orwell’s, Zamjatin’s, Huxley’s anti-utopias— it evolved into a genre unto itself, with its own aesthetics and its own audience. From speculation and warning against the distorsion of civilization, it consolidated into an self-referential and decadent genre. So, insomuch as it feeds on the fruit of a gloomy aesthetics, a social and human environment gone to seed, a string of pessimistic (but eventually consoling: Stories may survive the end of the world as we know it) tenets, solarpunk proclaims an incurable optimism not only of the setting, but also of the narrative mechanism that tells it, the fiction.

The word solarpunk first appeared twelve years ago in the blog Republic of the Bees, as a semantic derivation from steampunk:

[…] a major difference between solarpunk and steampunk is that solarpunk ideas, and solarpunk technologies, need not remain imaginary, and I indulge a hope of someday living in a solarpunk world. Another similarity between the genres is a cynical, film noir, sense of politics. I find it very unlikely that a transition to renewable energy can be accomplished without serious political fights between the good citizens of the world and corrupt forces attempting to advance their own personal gain. The current political efforts to subsidize the production of ethanol as an alternative to fossil fuels is only one example of the corruption that will need to be overcome.

Republic of the Bees blog

Right from this first appearance, solarpunk presented itself as an alternative to the current model of development: globalization, the current stage of capitalism. This characteristic remains important today, in fact it is strengthened by the awareness of the looming climatic disaster.

«Climate change is global-scale violence, against places and species as well as against human beings. Once we call it by name, we can start having a real conversation about our priorities and values. Because the revolt against brutality begins with a revolt against the language that hides that brutality.»

Rebecca Solnit

This optimistic vision, with its deep ideological impact, has immediately turned into a specific aesthetics, propagated above all through visual arts; an architecture which imitate the forms of nature[1], an iconography which commences from organic and inorganic becoming symbiotic, like in cyberpunk, but does not portend the reification of the human, the hi-tech invasion of the body’s boundaries, the cyborg, but on the contrary the end of the eternal strife between natural and artificial, the removal of the boundary between vegetal and mineral, the recycle and the reuse, the availability of virtually inexhaustible energy, cheap and with no environmental impact: a new stage of civilization, finally democratic and sustainable: in a nutshell, the end of anthropocene[2].

Right from its name, it is clear the reference to alternative energy sources. Environmentalism, degrowth, sustainability, forms of social organization based on sharing and on a local rather than State-like scale, nanotechnologies as a new way of conceiving and using scientific progress, are only some of the themes potentially making solarpunk the new utopia for 21st century.

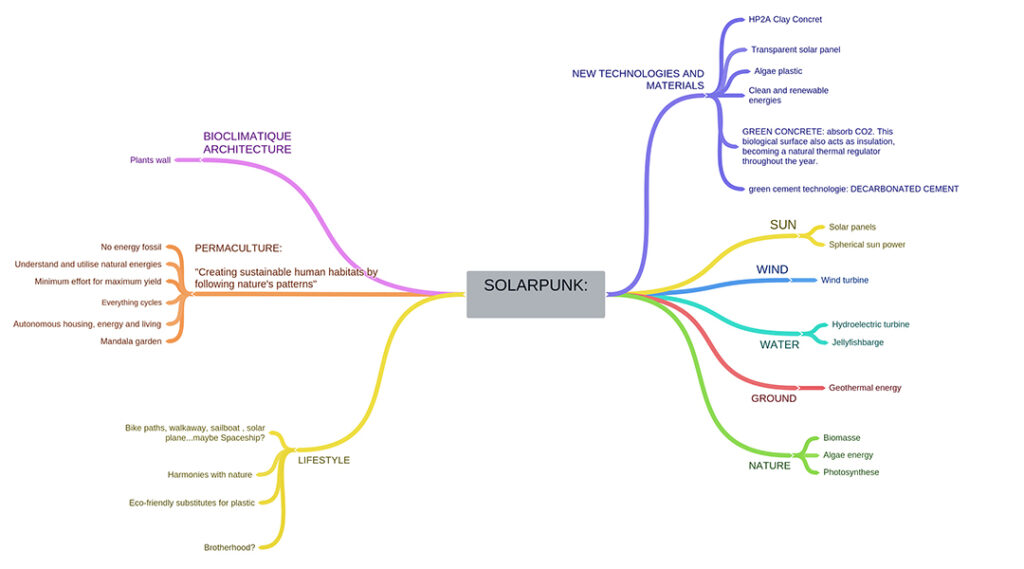

Infographics by Maxime Schilde, from Artstation

As you can read in the infographics, the core of the solarpunk concepts branches out reaching its feelers in many directions, combining imagination into daily, practical actions. So we see it surfacing in a lifestyle respectful of the environment and as little impacting as possible, in designing street furniture with an eye to regulating climate, temperature, health and mobility, in a housebuilding integrated with environment, in designing new eco-compatible technologies and materials, in the search for sustainable energies for the environment and the economy.

But the infographics has overlooked the aforesaid visual arts, which have found a fertile terrain in the web, and above all literature.

What is happening in literature?

On 17th September 2020, during the first live event via Facebook from Stranimondi[3] 2020, Giorgio Raffaelli, Matteo Meschiari and Alessandro Vietti, basing on pamphlet “Antropocene fantastico”[4] tried to imagine what directions a literature may follow when it tackles themes from the contemporary historic period, which recently Donna Haraway has defined with a more interesting etymology “Capitalocene”[5]. During the live event a call to action has been expressed for authors to take in charge the urgency of a literature with proposals for an after-crisis world; an essential call to action for whoever has conscience of the looming future, and at the same time believes in the power of art in shaping society.

This trust is nothing new in science-fiction; social science fiction was a forerunner of this, and nearer to us in time, without straying from the ecological roots of solarpunk, we have Octavia Butler, mother of afrofuturism, with Lauren Olamina, main character of the short Earthseed cycle, composed by only two novels,[6] which, like the remainder of her production, unifies warnings from dystopia with speculative necessities from utopia, creating a “Mixtopia”[7] and blazing thirty years in advance the trail for the coming solarpunk.

It is worthwhile to remember how the harbingers of this urge to think about a positive tomorrow can already be found in the “heroines who do not limit themselves in trying to survive, but also to build for the communities and the future”[8].

If social narration has the epistemic function of triggering processes of elaborating, interpreting, understanding, analysis, memory of experiences and facts, the next step, for entertainment narrative, is a concrete proposal of a change in speculative fiction. Women writers from the Seventies of last century have effectively probed different genres, but it is between utopia and dystopia that heroines have been able to highlight imaginations and commonplaces of womanhood, criticizing their socio-cultural construction and as a consequence developing worlds where women possess a subjectivity and an independence of their own.

The trustful, saving work of these heroines has often turned towards devising escape routes from an oppressed world and paths for healing dedicated to future generations. Let us remember then, and just as an example: Vaster than the empires and more slow by Ursula K. Le Guin, and The Forbidden Words of Margaret A., by L. Timmel Duchamp. Often intersectional demands are expressed, so paving the way for anti-capitalist, subversive, decolonisation narratives, inclusive towards the “other”, also meaning the non-human, eventually resulting in proposals which, in a nutshell, are solarpunk.

Since Octavia Butler’s Nineties until today, what has happened in the world? A large part of dystopic scenarios have become real; the invitation to speculation has turned into a call to arms, as stressed by Vietti and Meschiari.

An essay by Barnosky and collaborators[9], published in the prestigious scientific magazine Nature in 2012 and the subsequent work by Ceballos (2015/17)[10] highlight how the sixth mass extinction on Earth is currently taking place.

If even this dystopia has been set loose, it is necessary to go for the long haul and prospect desirable and necessary imaginations.

Seeds for the future

The term solarpunk contains two seeds: solar and punk. As literary genre, it has the dignity and the germinative power apt to speculate on all ecological and social struggles of today, of the near and the remote future, shaking off the unfaithful veil its detractors are already weaving. Hence, if solar is a cure for Gaia, intended as James Lovelock assumed her[11], punk is a commitment to a revolution from below, an Archimedes’ lever to unhinge all juxtapositions which are dooming our society: richness-poverty, man-woman, human-other, colonialism-migrations, extractivism-conservation, etc.

Solarpunk speculations may be defined as backcasting techniques because they show fractures in today’s status quo narrating desirable futures. In this regard, we can mention Critter, figurazioni, futuri. Tra mito, arte e (fanta)scienza di Roberta Colavecchio[12]:

«Europe, 2050. The old continent, renamed Eneuropa, presents a reorganization of its States based upon the sources of renewable energy—The new Europe is a more safe, happy and politically stable place.»

This paragraph has not been extrapolated from a solarpunk story: in fact it is a research project supported in 2010 by the European Climate Foundation in collaboration with several international institutions: Roadmap 2050, a practical guide to a prosperous low-carbon Europe.

Underlying to such collection of technical data is the narration of an imaginary future Europe, disjointed with the one of the Old Continent’s current economical and geopolitical arrangement. A bridge between fiction and mass adoption of a new world consistent with it, the map of Eneuropa suggests the use of science (fiction) codes to figure out practices meant for the construction of new, other and not apocalyptical world scenarios.

After few paragraphs, Colavecchio goes on about solarpunk genre: “In a social and cultural context threatened by the monsters of Anthropocene (Capitalocene) and driven by a fast technological and digital progress, the organization of a constructive response, which looks to the future with optimism, seems to assume capital importance to those who adhere to the recent creative movement known as Solarpunk.”

If narrative and essay are already delving into solarpunk, as several proclamations and “manifestos” show, also by Italian authors, what is happening in the world regarding our daily practices?

Best practice

Olga Solombrino in Femminismi futuri deals with decolonisation and equal opportunities (meant between rich-poor, colonialists-colonised) in the Palestinian territory. She shows a work by Vivien Sansour, the Queen of Seeds, in the town of Beit Jala, in the heart of the occupied Palestinians territories, wastelands which once were a paradise for biodiversity. This Palestinian anthropologist and artist realized the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library, “an archive created to contrast the loss of the rich traditional variety of crops and seeds, to preserve the ancient varieties and modes of cultivation, to narrate stories witnessing the properties of seeds and with them the imprint of History, to explore a new form of survival in the future”.

Anyway, storage and preservation of old vegetal varieties is a common necessity in agriculture both on a local level and on state level; several Italian institutions are tasked with such research effort (meant as an effort to recover ancient cultivar), classification, storage and planting. See as an example the essay Ispra: Frutti dimenticati e biodiversità recuperata.

To plant trees, as Wangari Maathi (Nobel Peace Prize 2004) did, or to throw bombs of seeds, is a deeply subversive practice, intimately democratic; it can be applied both to the daily care towards our planet and all living species who inhabit it, and to an intellectual speculation which could show us a way to ferry our holobiome beyond the damages already suffered and those it could still suffer. Solarpunk is the hand sowing seeds in the conscience of the readers.

Why don’t we have a great solarpunk author yet?

In the past, –punk literary movements obtained great renown thanks to the success of one work which shaped the readers’ taste, followed and imitated by others (not a negative principle at all) until a new subgenre was born: Neuromancer was the spark for cyberpunk, The difference engine triggered steampunk. Therefore what, how many, who are authors, authoresses and novels of solarpunk? We are in a bind here, because, to be sincere, solarpunk is much talked about but not much written.

It is talked about mostly thanks to a captivating aesthetics, exhibiting pictures of buildings covered with lush greenery, cities dotted with green, futuristic means of transport built with sustainable technologies, landscapes quite remote from the inhuman urban agglomerations which make cyberpunk imagination so ugly. Little solarpunk has been written, on the other hand; sure, there are Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140 and Pacific Edge, and Cory Doctorow’s Walkaway as well (these last two not translated in Italy), but neither author can be completely associated with the genre; there are some collective anthologies, such as the books edited by the American writer Sarena Ulibarri, or Elly Blue’s anthologies of feminist bike science fiction[13] and some more books, especially the first collection in absolute having the word in the title, Brazilian Solarpunk, Histórias ecológicas e fantásticas em um mundo sustentável (2012). In Italy there is Francesco Verso’s Camminatori saga[14]: Verso is also editor of an anthology gathering authors from all over[15], and was first to start talking about this most recent version of climate fiction.

Solarpunk is a method of imagining a better future, based around sustainable technologies and cooperative (rather than competitive) lifestyles. It’s “punk” because the mainstream narrative is that we’re headed toward disaster and dystopia; solarpunks refuse to accept that’s the only future available.

Sarena Ulibarri

We are at a turning point. Dystopia runs to stand still, it is by now but a subgenre of young adult; readers are fed up with negative visions, escaped from the pages of speculative fiction only to end up in the papers, in the news, in the conscience of the most aware among the inhabitants of this planet. This is the moment when literature must do its part, which is to conjecture scenarios, to show the way, to create the future before it materializes. It would not be the first time that writers create a world which science later makes real.

And if solarpunk has the power to bring us even one day nearer to the shining utopia it can describe, then we must get ready to do anything for it to become the science fiction of next years.

Romina Braggion & Franco Ricciardiello, traslated by Antonio Ippolito

Notes

[1] See for example the visionary urban renewal projects of the Belgian architect Vincent Callebaut, updating the movements that at the turn of the nineteenth and 20th century imagined the fantastic cities that industrial progress promised for the near future.

[2] In the 1960s, Soviet scientists were the first to use the term anthropocene to indicate the most recent epoch of the Quaternary; today we generally refer to the limited geological era characterized by the impact of human civilization on the planet—a geological era in a very broad sense, considering that it would start from the end of the Second World War.

[3] The yearly Festival of Fantastique in Milan.

[4] Matteo Meschiari, “Antropocene fantastico. Scrivere un altro mondo”, Armillaria, 2020

[5] Donna Haraway, “Staying with the trouble – making kin in the Chthulucene”, 2016

[6] Octavia Butler, “Parable of the Sower”, 1993, “Parable of the Talents”, 1998

[7] “Mixtopia” is a word created by Giuliana Misserville in “Chiamiamola Mixtopia”, review “Leggendaria” n. 143, 2020.

[8] Giulia Abbate, “Trionfano nuove eroine, guaritrici della specie”, review Leggendaria n. 143, 2020

[9] Barnosky A.D., Hadly E.A., Bascompte J., Berlow E.L., Brown J.H., Fortelius M., Getz W.M., Harte J., Hastings A., Marquet P.A., Martinez N.D., Mooers A., Roopnarine P., Vermeij G., Williams J.W., Gillespie R., Kitzes J., Marshall C., Matzke N., Mindell D.P., Revilla E., Smith B.A., Approaching a state shift in Earth’s biosphere, Nature 486 (7402):51-57.

[10] Ceballos G., Ehrlichb P.R., and Dirzo R., Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines, 2017, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114 (30): E6089–E6096; Ceballos G, Ehrlich AH, Ehrlich PR, The Annihilation of Nature: Human Extinction of Birds and Mammals, Johns Hopkins Univ Press, Baltimore 2015

[11] James Lovelock, The vanishing face of Gaia (2009)

[12] In Femminismi Futuri, a cura di Lidia Curti, con Marina Vitale e Antonia Ferrante, Iacobelli Editore, 2019

[13] Dragon Bike: fantastical stories of bicycling, feminism & dragons; Bikes not Rockets: intersectional feminist bicycle science fiction stories; Bikes in Space: feminist bicycle science fiction; Biketopia: feminist bicycle science fiction stories in extreme futures, Microcosm publ., Portland, Oregon.

[14] “I Pulldogs” (2018) and “No/Mad/Land” (2019), Future Fiction publ.

[15] “Solarpunk. Come ho imparato a amare il futuro”, Future Fiction 2019

Comments are closed